This is Part III of a four-part (I, II, IV) series on the early life of Heracles. In Part II, we left off with Heracles completing his fourth Labor. This week, we will examine Labors five through eight and investigate the nature of gods and demi-gods in Greek Mythology. Specifically, we will take a close look at King Minos of Crete and Ares, god of war.

Labor 5: The Augean Stables

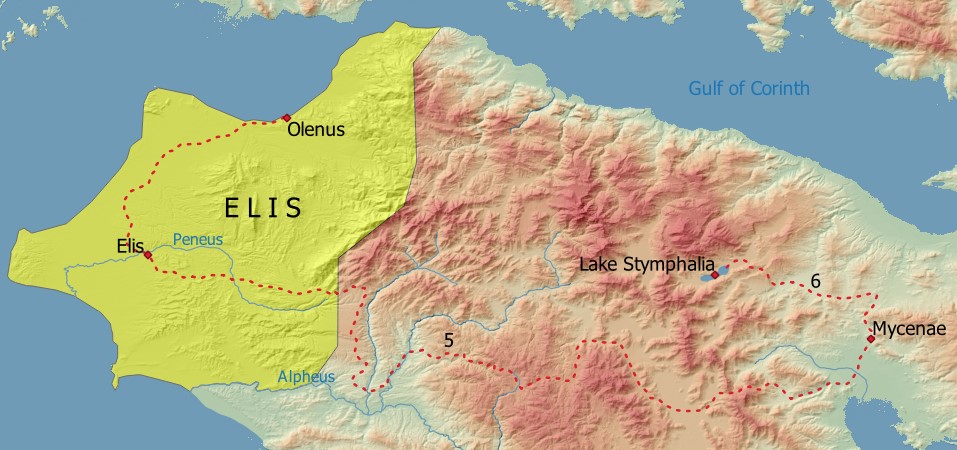

For his fifth Labor, Eurystheus sent Heracles to clean the stables of King Augeas of Elis. When Heracles arrived in Elis and saw the filthy stables, he told Augeas that he could clean them in a single day. For this work, Heracles asked for ten percent of Augeas’ cattle. Incredulous that the stables could be cleaned so quickly, Augeas agreed.

So Heracles started digging. Not the manure in the stables, but rather channels near the Alpheus and Peneus rivers. Heracles used these channels to divert the rivers and flood the stables. This surely cleaned out the dung – and presumably inundated the surrounding countryside – and Heracles duly asked for his payment.

But King Augeas (perhaps seeing the devastation of his flooded land) refused to pay him. This was despite the fact that his own son, Phyleus, was a witness to his agreement with Heracles. Phyleus testified against him, so Augeas banished both his son and Heracles from his kingdom. It’s good to be king.

Heracles traveled to the city of Olenus where he found King Olenus’ daughter about to marry a Centaur. Heracles, having none of that, killed the Centaur on his wedding day.

If these myths tell us anything, it’s that Heracles did not like Centaurs.

From Olenus, Heracles returned to Mycenae claiming a job well done. But Eurystheus refused to count this Labor because it was done for hire. So that was a whole lot of work and devastation for nothing. But at least there was one less Centaur around.

If you’re counting, at this point Heracles performed five Labors, but Eurystheus discredited two of them. So Heracles still had seven more to do in order to attain immortality.

Labor 6: The Stymphalian Birds

For his next Labor, Eurystheus sent Heracles to Lake Stymphalia where countless birds had taken refuge. And apparently this was a problem. We are told that the birds flocked to the lake because they were being preyed upon by wolves.

Pondering how best to get these birds to leave the lake, Heracles fashioned a bronze rattle and made a terrible noise to frighten them. The birds took flight, and Heracles shot them out of the sky with his poison-tipped arrows. In this way, the lake was rid of the birds.

Unfortunately, there is not much information about this Labor, but once again we can speculate that Heracles was not actually fighting birds. For one thing, wolves are not known to hunt birds. And it is dubious that a large number of birds on a lake would ever be a major problem for the King of Mycenae.

Labor 7: The Cretan Bull

With the Stymphalian Birds vanquished, Eurystheus sent Heracles to fetch the Cretan Bull. When Heracles arrived on Crete, King Minos told him to catch the bull himself. Heracles captured it, loaded it on his ship, and returned to Mycenae. But the ungrateful Eurystheus promptly let the bull go free. At this point it seems obvious that Eurystheus was trolling Heracles.

We are told that the bull roamed the countryside and traveled to Sparta and all of Arcadia before traversing the isthmus and arriving at Marathon, where it subsequently terrorized the inhabitants.

In a twist of fate, this bull would later kill King Minos’ son, Androgeus. His untimely death would cause a rift between Crete and the kingdom of Athens.

King Minos

But before we move on to the next Labor, let’s pause to take a look at King Minos.

We are told that King Minos was the son of Zeus and Europa, and the elder brother of Sarpedon and Rhadamanthys. When the former King of Crete, Asterion, died, Minos assumed the throne and banished his brothers from the island.

But here we encounter a major problem with mythological chronology. Minos’ mother, Europa, was a sister of Cadmus, the first King of Thebes. Because Heracles was born in Thebes we know that Cadmus lived at least four generations before Heracles. Moreover, various chroniclers indicate that Cadmus lived more than 200 years before Heracles.[1] Yet Cadmus was Minos’ uncle. This begs the question: How could Minos have lived long enough to meet Heracles? How can we make sense of a king who lived several centuries?

Ancient scholars supposed that there were actually two separate kings of Crete named Minos: Minos I and his grandson Minos II. The myths of Minos describing him as a great lawgiver were attributed to Minos I, and myths of Minos described as a cruel tyrant were attributed to Minos II. However, this distinction is never made in any of the myths themselves. It seems that there was only one King Minos, and he lived an incredibly long time.

It should be noted that this problem doesn’t just apply to King Minos, but many mythological figures. All attempts to make sense of mythological chronology have failed; treating mythological figures as real human beings inevitably runs into this problem. And since the oldest person to have ever lived was only 122 years old, it is extremely difficult to take myths at face value.

In the previous posts we have noted several examples of personification in myth. Could this also be the case with King Minos?

Well, we know that King Minos was unanimously identified as a King of Crete, and specifically the King of Knossos. Knossos was the largest city on the island of Crete up until the end of the Bronze Age. And it was the center of power of the aptly named Minoan civilization.

The ancient historian Thucydides claimed that Minos was the first known king to build a navy, and he used this navy to conquer the islands of the south Aegean Sea and clear the sea of pirates. He also claimed that Minos expelled the original rulers of these islands and appointed his own sons as governors.[2] This claim is echoed by the historian Herodotus.[3]

We can actually map all mythological mentions of King Minos and his descendants.[4,5,6,7,8]

As you can see, all geographical mentions of Minos and his children are on Crete and the islands of the Aegean Sea (and Megara).[A]

Minoan Civilization

Ever since Sir Arthur Evans excavated the Palace of Knossos in 1900, historians have pondered whether the myths of King Minos contain a kernel of truth. Centered on the island of Crete and the Aegean islands, a long-lost Bronze Age civilization was discovered. The ‘Minoan’ civilization was named by Evans after the mythical king of the island.

We don’t know what the people of Crete called themselves, but Egyptian records from the Bronze Age refer to the island of Crete as Keftiu.

The Minoan civilization spread its influence across the southern Aegean Sea and reached its height around 1750 – 1450 BC. Its influence can be seen in archaeological sites on the islands of Kythera, Melos, Kea, Thera, Samos, Karpathos, Kasos, and Rhodes. Minoan objects have also been unearthed on the Greek mainland, in western Anatolia (at Iasos and Miletus), Cyprus, Egypt, and the Levant.

Greek Mythology describes Minos as a king who ruled Crete and the islands of the south Aegean who lived several centuries.

This parallels our modern understanding of the Minoan civilization which was centered on Crete, spread its influence throughout the islands of the south Aegean, and lasted several centuries.

In myth, King Minos may very well personify what we now call the Minoan civilization. But by itself, this is impossible to prove for certain.

Labor 8: The Mares of Diomedes

Let’s now return to Heracles.

For Heracles’ eighth Labor, Eurystheus sent him to steal the man-eating mares of Diomedes.[B] Diomedes was the son of Ares and Cyrene, and the king of the Bistones, a warlike Thracian tribe. Heracles sailed there and raided Diomedes’ stables, driving the man-eating horses back to his ship. When the Bistones counter-attacked, Heracles gave the mares to his friend Abderus.

But poor Abderus was killed by the monstrous horses. So Heracles slew Diomedes and fed the Thracian king to his mares, and the rest of the Bistones fled. And after the battle, he founded the city of Abdera at the spot where Abderus had died.

Heracles brought the mares back to Eurystheus, and once again Eurystheus just let them go. The mares came to Mt. Olympus where they were later destroyed by wild beasts.

Ares and Thrace

In Greek Mythology, Ares is always associated with the region of Thrace. And here are some examples:

Odyssey 8.359:

So saying, the mighty Hephaestus loosed the bonds and the two, when they were freed from that bond so strong, sprang up straightaway. And Ares departed to Thrace.

Iliad 5.431:

And baneful Ares entered amid the Trojans’ ranks and urged them on, in the likeness of swift Acamas, leader of the Thracians.

Iliad 13.296:

And even as Ares, the bane of mortals, goes forth to war, and with him follows Phobos, his son, valiant alike and fearless, that turns to flight a warrior, were he never so staunch of heart – these two arm themselves and go forth from Thrace.

And the playwright Euripides calls Ares “the shield-bearing lord of Thrace“.[9]

In mythology, the Thracians are always described as a warlike people, so it is fitting that Ares was associated with this region. It comes as no surprise that Diomedes, the king of a Thracian tribe, was said to be a son of Ares.

Yet Ares was not a Thracian god. It was traditionally thought that worship of Ares was imported to Greece from Thrace, but there is absolutely no evidence of the Thracians worshipping Ares or even a god similar to Ares. His name and attributes are all Greek inventions.

In the Late Bronze Age, Thrace worshipped a Sun god. Worship of a Great Mother Goddess in Thrace is also known from this time.[10,11] But the worship of a god of war such as Ares is unattested.

The word Ares in Greek actually means ‘battle’, or ‘war’. And because the Greeks perceived the Thracians as being an aggressive and warlike people, the Greeks deemed them to embody the spirit of Ares.

Right now, it is only important to know that Ares is associated with Thrace. And we will see in future episodes that each god has a particular affinity for their own specific region.

Conclusion

In the case of King Minos, it is certainly curious that he and his descendants inhabit the same areas reached by Minoan culture. And considering the fact that Greek Mythology must originate in the Bronze Age, the similarities seem more than coincidental.

It seems unlikely that the stories of King Minos are completely fabricated and arbitrary. Treating Minos as the personification of a kingdom rather than a king has the advantage of explaining his incredible longevity. But without more information, it is difficult to assess the connection between Minos and the Minoan civilization.

And in the case of Ares, it is clear that he is firmly associated with Thrace. Now whether he personifies the region of Thrace (or the Thracian people themselves) is not yet possible to prove.

In any case, it seems quite likely that personification runs deep in Greek Mythology. Upcoming episodes will explore the geographic affinities of each of the Greek gods. And by analyzing their interactions with each other we will begin to unravel the secret history of the Aegean Bronze Age encoded in myth.

Notes:

[A] We are told that Minos gained control of Megara at one point during his reign. It should also be said that the inclusion of Thasos comes from Bibliotheca 2.5.9 which describes the kidnapping and forced migration of two of Minos’ sons by Heracles (discussed in Part IV). The map does not show Camicus (in Sicily) where Minos allegedly died [Bibliotheca E.1.14], nor Libya where his daughter Acacallis later migrated [Argonautica 4.1485].

[B] Diomedes of Thrace, who we are referring to here, should not be confused with Diomedes of Argos.

[C] In the Iron Age, “Thrace” would come to represent a larger region which spread further inland from the coast. But in the Bronze Age, the Greeks were only familiar with the coastal region of Thrace.

Sources:

[1] Parian Chronicle; Herodotus 2.44.4

[2] Thucydides History of the Peloponnesian War 1.4

[3] Herodotus Histories 1.171, 3.122, 7.171

[4] Pseudo-Apollodorus Bibliotheca 2.5.9, 3.1.2-3, 3.15.7-8, E.1.9, E.3.3, E.3.13, E.6.10

[5] Homer Iliad 2.656, 17.505, 17.597, 18.468

[6] Homer Odyssey 11.225, 19.164

[7] Apollonius of Rhodes Argonautica 4.421

[8] Bacchylides Epinacrians 1.115

[9] Euripides Alcestis 498

[10] Thrace & the Thracians, p. 17-36, by Alexander Fol and Ivan Marazov

[11] Ancient Gold: The Wealth of the Thracians: Treasures from the Republic of Bulgaria, p. 86-91, Fol et al. 1998