This is Part I of a four-part series (II, III, IV) on the early life of Heracles. In this series, the nature of heroes, monsters, gods, and demi-gods will be examined. We will explore where these concepts came from, and what can they tell us about how myths were created.

You’ll notice that I will be using the Greek name Heracles rather than the more commonly used Latin name Hercules. This is mostly a matter of preference, but it highlights the fact that we will be talking about Greek Mythology, not Roman Mythology (they are not the same!).

And as most people are familiar with Heracles (or Hercules), this seems like a good place to start our journey.

This episode, Part I, introduces the story of Heracles and focuses on names and geography. The main idea is to consider how geographical information may be encoded in myth.

Part II examines the origins of monsters, and the possible historical origins of such stories.

Part III explores the nature of gods and demi-gods, and what they represent.

And Part IV takes us to the ends of the known world.

These four episodes will provide the foundations for exploring Greek Mythology in an objective way. This is absolutely essential if we are to uncover the historical origins of these ancient stories.

Birth of Heracles

Our story begins in Mycenae, the most powerful city in Greece in the Late Bronze Age, and namesake of the Mycenaean civilization.[A]

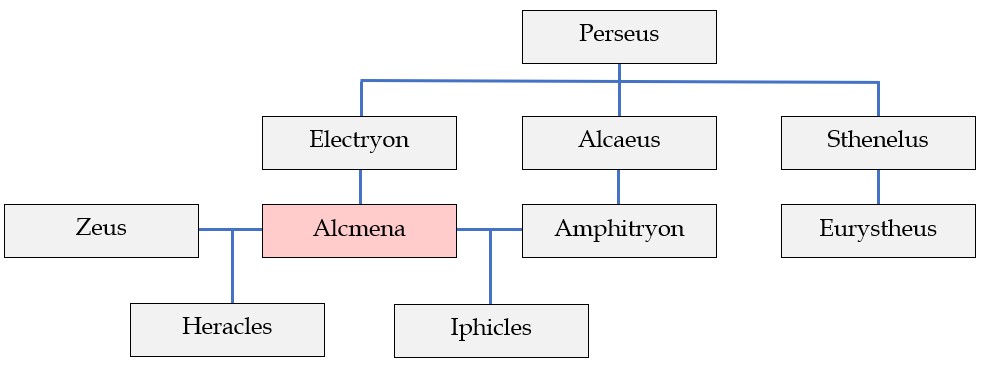

The king of Mycenae, Electryon, has just died at the hands of his own nephew, Amphitryon. Acting quickly, Sthenelus, Electryon’s brother, seizes the throne and banishes Amphitryon from the kingdom. And Alcmena, Electryon’s daughter, flees with Amphitryon, her lover, to the city of Thebes.

As Electryon’s only heir, Alcmena, is the sole custodian of her father’s estate. This means that her first-born son stands to inherit the Kingdom of Mycenae.

But Sthenelus, now king, argues that the kingdom should be passed down to his own son.

It is this dramatic backdrop in which the story of Heracles begins.

Zeus, acting as arbitrator over the issue of succession, ruled that the next-born descendant of Perseus would be the heir to the Mycenaean throne.

But Zeus did not make this judgment without bias. For he had recently wooed Alcmena while her lover Amphitryon was away fighting pirates. Alcmena was now pregnant with two sons: Heracles, the son of Zeus, and Iphicles, the son of Amphitryon.

Zeus intended Heracles to be the next king of Mycenae.

But Hera, always scheming against her husband Zeus, made sure that Sthenelus’ son Eurystheus was born first. She did this by summoning the help of the Eileithyia, the goddesses of childbirth, to make sure that Eurystheus was born after only seven months.

Eurystheus, not Heracles, became the new king of Mycenae.

And so even at birth, Hera hated Heracles, an illegitimate son of Zeus and a living reminder of her husband’s infidelity. Hera would attempt to thwart his goals all his life.

Youth and Early Heroic Deeds

Alcmena gave birth to Heracles and Iphicles in Thebes. And when Heracles was an infant, Hera sent two serpents to kill him. But Heracles strangled them in his crib. It is then that Amphitryon knew that Heracles was the son of Zeus.

Amphitryon taught Heracles how to drive a chariot. Others taught him wrestling, archery, fencing, and how to play the lyre — although Heracles killed his music instructor with the lyre. This would be a sign of things to come.

Heracles was tried for murder, but was acquitted due to some obscure, ancient law.

To prevent him from causing any more trouble, Amphitryon sent his stepson to the cattle farm.

But his penchant for violence did not subside, and Heracles got his first big break when King Thespius came requesting his assistance. The Lion of Mt. Cithaeron was harassing cattle in the area, and Thespius asked Heracles to kill it. But Thespius had ulterior motives, as he desired for his grandchildren to be fathered by Heracles, who was now eighteen years old.

So for 50 days Heracles climbed Mt. Cithaeron to fight the lion, and each night he returned to the town of Thespiae where King Thespius gave him one of his daughters to sleep with. Exhausted from fighting the lion, Heracles thought that it was the same woman each night.

After 50 days, Heracles finally killed the lion, dressed himself with its skin, and donned its scalp as a helmet.

Sick of living on the cattle farm where there was nothing left to fight, he came back to Thebes.

At the time, Thebes was paying a handsome tribute of 100 heads of cattle per year to the city of Orchomenos, situated on the far side of Lake Copais. So Heracles – perhaps feeling invincible after killing a lion – cut off the ears, noses, and hands of the heralds from Orchomenos who were sent to collect the tribute. He then put ropes around their necks and told them to go back to Orchomenos.

Outraged, King Erginus of Orchomenos declared war on Thebes. But Heracles, with weapons from Athena, defeated Orchomenos’ army. Some say that he dammed Lake Copais and flooded the city of Orchomenos. In the process, he killed King Erginus and forced them to pay double the tribute to the Thebans. In this fighting, Amphitryon died, and the city of Orchomenos was burnt to the ground.

As a reward for defeating Orchomenos, King Creon of Thebes gave his daughter Megara to Heracles in marriage. And Megara bore him three sons. Heracles also received a sword from Hermes, a bow and arrows from Apollo, a golden breastplate from Hephaestus, and a silver robe from Athena.

So by the time Heracles was eighteen he had already killed a lion, razed a city to the ground, fathered 53 children, and received weapons from the gods. Life moved fast in the Bronze Age.

The Path to Immortality

But Hera drove Heracles insane, which caused him to murder his children begotten by Megara, as well as two of Iphicles’ children for good measure.

But despite these heinous crimes, Heracles was purified of his sins by Thespius. He was nonetheless exiled from Thebes.

Banished from his homeland, Heracles consulted the Oracle at Delphi to see where he should live. The Oracle told him to live in Tiryns and serve King Eurystheus of Mycenae, his cousin. The Oracle instructed him to perform ten heroic Labors for Eurystheus, stating that once this service was over he would gain immortality.

Eponyms and Personification

Already the story of Heracles features two eponyms: Thespius and Megara. Thespius was the king of Thespiae, and Megara was a princess of Thebes.

Now, it seems obvious that the city-state of Thespiae was named after King Thespius. But was the town of Megara (and region of Megaris) named after the Theban princess Megara? The answer is not so obvious. But one cannot deny that it is curious.

On its face, this question may seem silly, but it is crucially important if we are to determine the origins of Greek Mythology.

In an absolute monarchy the actions of King Thespius would be identical to that of the kingdom of Thespiae. Thus, in myth, there would be a clear distinction between Thespiae the place and Thespius the man.

So in the same way, we might ask ourselves if references to princess Megara instead refer to the region south of Thebes. If myths do in fact personify geography, then princess Megara herself may represent Theban control over this region.

We may also remember the information that Athena gave weapons to Heracles to fight against Orchomenos. We might imagine the goddess Athena bestowing these weapons upon the army of Thebes. But perhaps Athena is simply personifying the city-state of Athens.[B] If so, this story might actually be telling us that Athens helped Thebes in its fight against Orchomenos.

We can see how viewing Greek Mythology from this perspective may provide significant geographical and political details to these stories. This is important if Greek myths are based on historical events.

Eponyms are important to recognize, as they will play a large part in our analysis of Greek Mythology. By understanding their patterns, we will discover geographic information encoded within the myths that appear to tell a vivid history of Bronze Age Greece.

Other Information

Notes

[A] The Late Bronze Age is dated to c. 1600 – 1100 BC.

[B] It is worth mentioning that the Greek name for Athens, Ἀθῆναι, is derived from the name of the goddess, Ἀθηνᾶ.