The Amazons continue to spur the imagination to this day, after more than 2,500 years. Legends of a defiant tribe of female warriors fascinated the ancients as much as they do today. From the Amazon Rainforest to Wonder Woman, they have left an indelible imprint on world culture.[A]

But who were these legendary women warriors? Did they really exist? And what can they tell us about Greek Mythology itself?

These are the questions that we will explore in this four-part series.

In this episode, Part I, we will attempt to answer the first question (Who were they?) by exploring their mythical history, geography, and society.

In Part II, we will take a close look at the geography of the Amazonian homeland.

Part III couples our geographic understanding with archaeological and historical evidence. Here, we will examine the evidence for the existence of Amazons.

Parts IVa and IVb explore where these legends came from, and what the Amazons can tell us about the origins of Greek Mythology.

If you like this content and want to know when a new episode is created, you can leave your email below.

I create this content with the hope that others may find it interesting. So if you know someone who would enjoy this site, please feel free to share!

Introduction

The curious thing about the Amazons is that unlike other tribes, heroes, and monsters, the Greeks never considered the Amazons to be mythical. The Greeks were unwavering in this regard. Ancient mythographers, historians, grammarians, and geographers alike persistently maintained that tribes of Amazons did indeed exist.

In this way they are unique: they bridge the gap from the mythical Heroic Age to the time of Classical Antiquity; from an age of oral storytelling to that of written text.

But they have yet to make that great leap from legend to historical fact. And indeed that jump is huge. But if we are ever to bring mythology into the historical realm – to understand that kernel of truth at the base of Greek Mythology, the Amazons are our best bet of doing so.

And so that is the aim of this series: to narrow that gap between history and mythology.

Geography of the Amazons

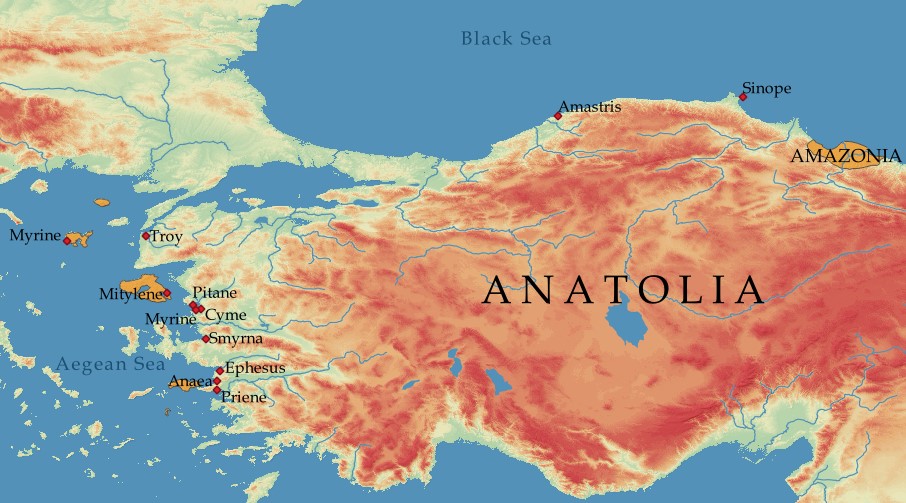

There appear to have been two main areas of Amazonian influence:

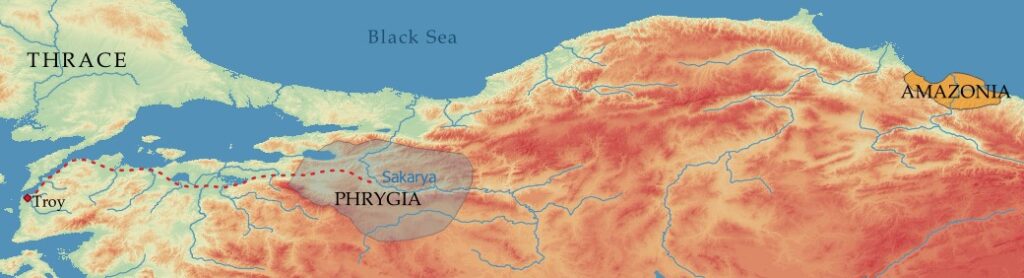

- Western Anatolia, including several northeast Aegean islands

- Northern Anatolia

We are told that the Amazons were driven from western Anatolia, while their presence in northern Anatolia persisted into the Heroic Age.[B] So by the time of heroes such as Heracles, Theseus, and Bellerophon, their homeland was confined to northern Anatolia (a region I will refer to as “Amazonia”).

The cultural memory of the Amazons was also preserved by many towns in western Anatolia whose coinage featured Amazonian queens.

Mythical Origins

But who were the Amazons, and where did they come from?

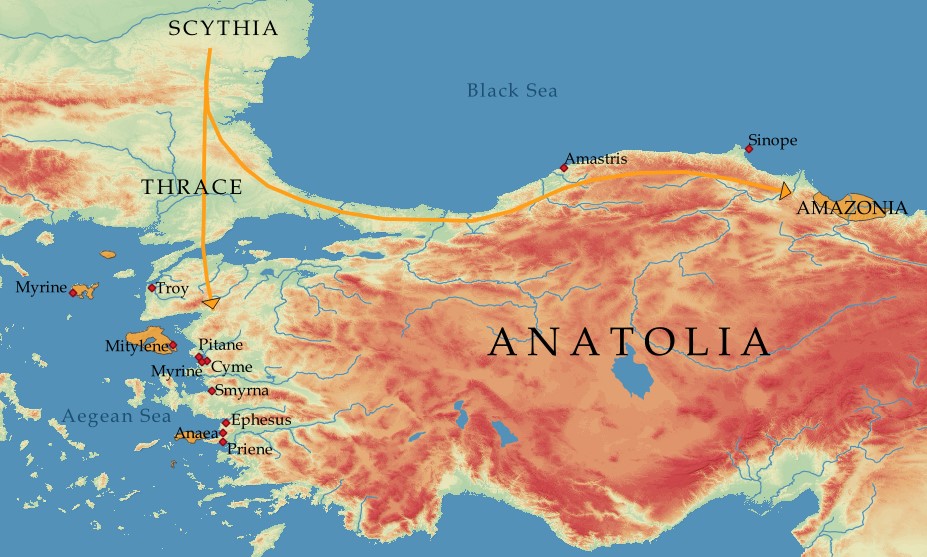

The historian Ephorus allegedly claimed that a band of Scythians had migrated from the lands north of the Black Sea and came to Anatolia, becoming the Amazons.[15]

The view that the Amazons were Scythians is shared by most ancient historians from Herodotus (5th century BC) to Jordanes (2nd century AD). The word Amazon itself likely comes from the ancient Iranian ha-mazan meaning “warriors”.[C] And the Scythians spoke an Iranian language.

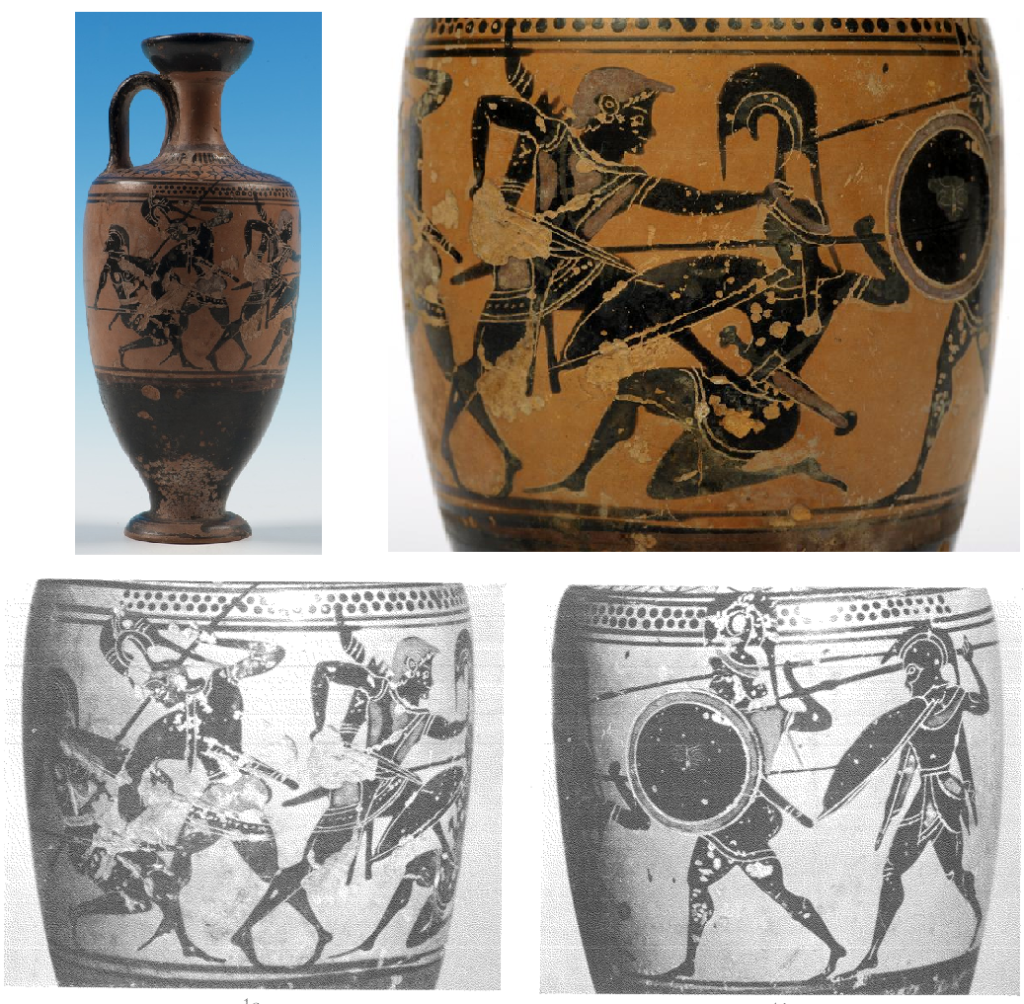

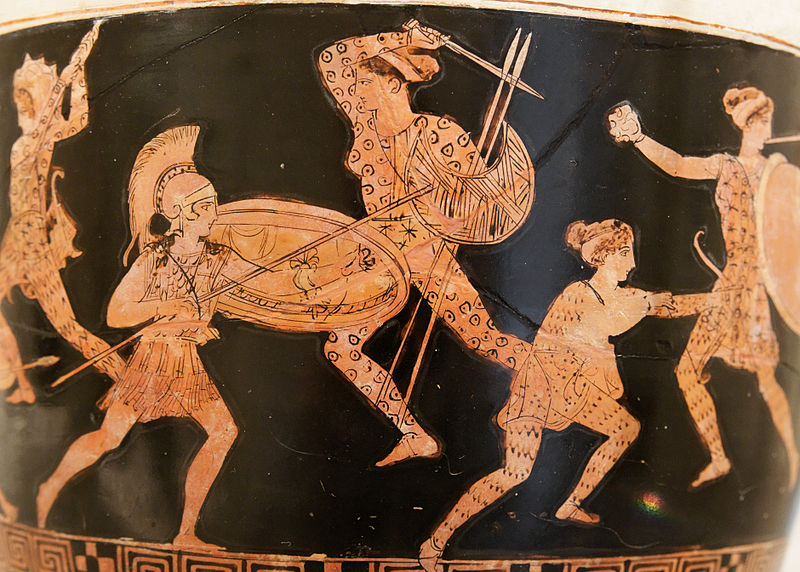

Yet there are other pieces of information which suggest that the Amazons were, at least partially, Thracian. For instance, Hecataeus of Miletus claimed that the Amazons spoke a Thracian dialect.[16] The Amazons were also commonly referred to as the “Daughters of Ares” (see Heracles Part III on the connection between Ares and Thrace). And in vase paintings the Amazons are frequently depicted with both Scythian and Thracian attributes.[17]

Whether they were Scythian, Thracian, or both, it seems that they migrated to Anatolia from the west.

The Amazons were said to have worshipped both Ares and Artemis. Yet it is unlikely that the non-Greek Amazons worshipped Greek gods. The Amazons’ worship of Ares and Artemis has been traditionally interpreted as a Greek way of explaining their warlike nature (Ares), female independence (Artemis), and expertise in hunting and archery (Artemis).

And whereas this may be true, I believe that this association goes a little deeper. Given that Ares seems to personify Thracian peoples, we might suppose a similar personification between Artemis and Scythian peoples. Thus, Amazonian worship of Ares and Artemis mirrors their Thraco-Scythian origins.

There is a lot of evidence to support this idea, and it is a topic which we are sure to get into in our series on the Trojan War. But it is worth keeping in mind for now.

Amazonian Society

So ancient scholars tell us that they were definitely Scythian, and possibly Thracian, but what do we know about Amazonian society? Where do legends of fierce female fighters originate?

The earliest mention of the Amazons comes from Homer. The Iliad refers to them as Amazones antianeirai.[18] The –es suffix in Amazones indicates that they were a tribe which consisted of both women and men.[E] But the word antianeirai is quite interesting, as its –ai suffix refers to a group of women. Antianeirai is usually translated as “man-hating”, but an equally valid translation is “equals of men”. Thus Amazones antianeirai can be translated as “The Amazonian people, whose women are equals of men”.[F]

So instead of a tribe consisting of only women, it seems that the earliest mention we have refers to an egalitarian tribe, or perhaps a matriarchal tribe if we take antianeirai to mean “man-hating”. In any case, based on the meaning of this phrase, it seems that men were indeed a part of Amazonian society.

There are in fact some Greek vase paintings which show men fighting alongside Amazons, but it is difficult to know who these men are. Are they Amazons themselves, or allies of the Amazons?

The ancient scholar Diodorus Siculus is apparently in agreement with Homer in his assertion that there were men in Amazonian society. He asserts the veracity of his information by prefacing what he has to say with this:

“But for our part, since we have mentioned the Amazons, we feel that it is not foreign to our purpose to discuss them, even though what we shall say will be so marvelous that it will resemble a tale from mythology.” [19]

Diodorus continues:

“Now in the country along the Thermodon River, as the account goes, the sovereignty was in the hands of a people among whom the women held the supreme power, and its women performed the services of war just as did the men.” [20]

And the rest of this passage is really worth reading to get an understanding of the legends surrounding the Amazons:

“One of these women was remarkable for her prowess in war and her bodily strength, and gathering together an army of women she drilled it in the use of arms and subdued in war some of the neighboring peoples. And since her valor and fame increased, she made war upon people after people of neighboring lands, and as the tide of her fortune continued favorable, she was so filled with pride that she gave herself the appellation Daughter of Ares.

She assigned the men to the spinning of wool and such other domestic duties usually performed by women. Laws were also established by her, by virtue of which she led forth the women to the contests of war, but upon the men she fastened humiliation and slavery. And as for their children, they mutilated both the legs and the arms of the males, incapacitating them from serving in combat, and in the case of the females they seared off the right breast in order to not be in the way [when throwing a javelin].”

So Diodorus was certainly of the belief that the Amazons were a matriarchal society, to say the least. He repeats some of these claims adding that the women administered the affairs of the state, and that they maintained their virginity until they had fought in battle.[21]

Strabo (1st century AD) gives a tamer description of the Amazons who lived right before his time:

“The Amazons spend the rest of their time off to themselves, performing their several individual tasks, such as plowing, planting, pasturing cattle, and particularly in training horses, though the bravest engage mostly in hunting and horseback and practice warlike exercises. The right breasts of all are seared off when they are infants so that they can easily use their right arm for every needed purpose, and especially that of throwing the javelin. They also use bow and sagaris and light shield, and make helmets, clothing, and war-belts (zosters) from the skins of wild animals.

They have two special months in the Spring in which they go up into the mountains which separates them and the Gargarians (a neighboring tribe). The Gargarians also, in accordance with an ancient custom, go up there to offer sacrifice with the Amazons and also to have intercourse with them for the sake of begetting children, doing this in secrecy and darkness, any Gargarian at random with any Amazon; and after making them pregnant they send them away; and the females that are born are retained by the Amazons themselves, but the males are taken to the Gargarians to be brought up; and each Gargarian to whom a child is brought adopts the child as his own, regarding the child as his son because of his uncertainty.” [22]

And in visual media, such as vase-paintings, the Amazons are often portrayed wearing trousers, leather caps, and zosters. They typically wield crescent moon-shaped hide-covered shields (pelta), Scythian bows, spears, axes (sagaris), and javelins. They are variously portrayed on foot, chariot, and horseback.

This is about all we know regarding Amazonian society.

Many ancient Greek historians give similar descriptions to Diodorus and Strabo. Namely that they seared off one of their breasts, mated once a year with a neighboring tribe, and either subjugated their men or mostly lived apart from them. We will address each of these mythic elements in Parts III and IV.

Mythical History

Now that we have covered what ancient scholars have to say about their origins and society, let’s examine their interactions with Greek heroes.

Heracles’ journey to the land of the Amazons is but one piece of their mythical history. Greek myths tell of their encounters with other heroes such as Bellerophon and Pegasus, Priam of Troy, and Theseus.

Bellerophon was a Greek prince who was sent to Lycia to serve King Iobates. King Iobates sent him to slay the monstrous Chimera, which he did with the help of his winged horse, Pegasus. After accomplishing this feat, we are told that he fought the insolent Solymi tribe and then the Amazons. With the help of Pegasus, he defeated them both.[23,24,25]

Nothing more is known about this fight between Bellerophon and the Amazons, but these Amazons presumably lived close to Lycia. This is nowhere near the Amazonian homeland, which indicates that the Amazons may have been dispersed throughout Anatolia.[G]

The Iliad gives another mention of the Amazons, as told by King Priam of Troy:

“I have journeyed to the land of Phrygia, rich in vines, and there I saw in multitudes the Phrygian warriors, masters of glancing steeds, and the people of Otreus and godlike Mygdon, that were then encamped along the banks of the Sakarya River. For I too, being their ally, was numbered among them on the day when the Amazons came, the peers of men.” [26]

It is important to note that even though this passage is usually taken to mean that Priam fought with the Phrygians against the Amazons, this is not explicitly stated. Just because they met the Amazons doesn’t necessarily mean that they fought against them. And considering that the Amazons would later come to Troy’s defense in the Trojan War, it seems likely that they were not enemies.

The story of the Amazons coming to Troy’s aid is described in an epic poem, the Aethiopis, which was composed around the same time as the Iliad. It tells the story of an Amazon named Penthesileia who arrived at Troy with twelve other Amazons. Achilles killed her, but when he removed her helmet he fell in love with her beauty. This tale is also told in Virgil’s Aeneid where Penthesileia came too late to help the beleaguered city.

Curiously, the Aethiopis claims that Penthesileia came from Thrace. But Quintus Smyrnaeus’ Fall of Troy clarifies that she was a guest in Thrace before coming to Troy.

The last mythic episode we have of the Amazons involves Theseus. Like Heracles, he also visited the land of the Amazons in northern Anatolia. But instead of killing and robbing their queen, he kidnapped and married her. A late tradition claims that in retaliation the Amazons invaded Athens. If I get to making a post about Theseus I will share my thoughts on this myth. But I will spare you for now.

Apart from these four stories, there are two Amazonian legends which deserve special mention. The first comes from Jordanes’ Getica which describes the Amazon invasion of Anatolia, Armenia, and Syria.[27] The second comes again from Diodorus who describes the accomplishments of the Libyan Amazons, not least of which was their successful war against the Atlanteans.[28] We will assuredly revisit these two myths at the end of our journey.

So as you can see, the Amazons were quite active during the Heroic Age. Outside of Amazonia they feature in myths near Lycia, Phrygia, Troy, Thrace, and Libya.

Conclusion

The Amazons appear to have been a Thraco-Scythian tribe composed of both women and men. The myths suggest that this tribe migrated through Thrace into Anatolia where it founded several cities, particularly on the coast of western Anatolia, northeastern Aegean islands, and northern Anatolia. This migration occurred well before the Heroic Age. Myths of the Amazons from this time describe them as a fierce matriarchal society that subjugated many kingdoms, large swaths of Anatolia, and their own men.

By the Heroic Age, the Amazons were driven out of these lands in western Anatolia and the Aegean islands. They made appearances in Lycia, Phrygia, Thrace, and Troy, but their homeland was reduced to northern Anatolia by the time of Heracles.

In Parts II and III, we will explore this homeland and the evidence for the existence of Amazons.

Notes

[A] The Amazon River (and Rainforest) was named by Spanish explorer Francisco de Orellana in 1542 after coming across the Icamiabas tribe of women warriors there.

[B] The Greeks believed that the fall of Troy signified the end of the Heroic Age and dated this event to c. 1200 BC. Therefore the Heroic Age must roughly correspond to the Late Bronze Age.

[C] It should be noted that this is the most likely etymology, but there are other possible etymologies. For instance, in the Circassian language Amezan means “The Goddess of the Forest”.

[D] Scythia was a catch-all term used by the ancient Greeks to denote the vast Eurasian steppes north of the Black Sea. Its borders were not defined, just as its peoples were not culturally homogeneous. Thus, in its most generic form, “Scythian” simply meant someone from Scythia.

[E] Examples of the –ai suffix: Nymphai = “(female) nymph”; Trooai = “women of Troy”. And examples of the -es suffix: Hellenes = “Greek people”; Trooes = “Trojan people”.

[F] This is in contrast to the strictly patriarchal society of ancient Greece where women were mostly confined to the house, kept from engagement in political affairs, and did not see combat.

[G] Knowledge of Amazonian geography may have been affected by Greek geographical bias, as the ancient Greeks would have had more frequent contact with coastal regions than inland regions. But as we are talking about mythical stories, there is no way to know for certain.

Sources

[1] Hecataeus of Miletus FHG fr. 212

[2] Plutarch Quaestiones Graecae 56

[3] Eusebius Chronicle 66.13

[4] Strabo Geographica 11.5.4, 12.3.21

[5] Pausanias Description of Greece 7.2.7-8

[6] Homer Iliad 2.811

[7] Diodorus Siculus Bibliotheca historica 3.54.1

[8] Stephanus of Byzantium Ethnica s.v. Amazones

[9] Pseudo-Scymnus Periodos to Nicomedes 986

[10] Scholiast on Apollonius Rhodius 2.946

[11] Ephorus FHG fr. 86

[12] Callimachus Hymn to Artemis 3.233

[13] Julius Caesar De Vita Caesarum

[14] Jordanes Getica

[15] The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women across the Ancient World, p. 43, Adrienne Mayor.

[16] Hecataeus of Miletus FHG fr. 352

[17] The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women across the Ancient World, p. 97, Adrienne Mayor.

[18] Homer Iliad 3.189, 6.185

[19] Diodorus Siculus Bibliotheca historica 2.44.3

[20] Diodorus Siculus Bibliotheca historica 2.45.1 ff

[21] Diodorus Siculus Bibliotheca historica 3.53.1

[22] Strabo Geographica 11.5.1

[23] Homer Iliad 6.144 ff

[24] Pindar Olympian Ode XIII 60 ff

[25] Pseudo-Apollodorus Bibliotheca 2.3.2

[26] Homer Iliad 3.184

[27] Jordanes Getica

[28] Diodorus Siculus Bibliotheca historica 3.52.1